The filter bubble is hot. In the aftermath of the 2016 U.S. elections, every self-respecting media organization appears to be writing stories about the existence of the filter bubble and its (presumed) harm to democracy. Times when the internet was thought of as a public sphere, an open forum for deliberation, feel long gone. Many blame the internet for creating filter bubbles, causing the 2016 campaigns to become as polarized as we have witnessed. Your filter bubble, Wired Magazine wrote, “is destroying democracy”. But did filter bubbles really exist during the 2016 U.S. elections? And if so, what did they look like?

What we did

To find out, we analyzed over 80 million tweets about the U.S. elections sent from September 26, 2016 onwards and investigated the media self-identifying Trump and Clinton supporters were linking to the most. Within this huge dataset, we limited our analysis of tweets sent between November 1st and November 15th, the week before and the week after the general elections. To what media were supporters of both candidates referring to in the heat of the moment?

You might be wondering: how do you find people who openly identify as either Trump or Clinton supporter on Twitter? We did so by looking for people who classified as such in their Twitter bio. About 35 thousand Twitter users within our data set had “#trump” in their bio, of whom approximately 86% can be considered pro-Trump. Clinton supporters were more difficult to find, as many people with “Clinton” in their bio were either anti-Clinton or, for instance, tweeting about the Clinton foundation. Hence, we looked for people with Clinton’s official campaign slogan “#imwithher” in their bio. We found 8 thousand Twitter users, of whom 100% actually identified as Clinton supporter.

By using a co-hashtag graph, we distinguished between two clusters of hashtags used within these groups of supporters: what we have come to call ‘conventiona’l hashtags and ‘fringe’ hashtags. The conventional hashtags of both candidates included the official hashtags used by the candidates and their campaigns, such as #VoteTrump #MAGA and #StrongerTogether. The fringe hashtags were primarily used by the more activist wings of both campaigns and included hashtags like #LockHerUp, #HillaryForPrison and #DumpTrump.

We eventually drew up four different lists of hashtags, of which we filtered out four different groups of Trump or Clinton supporters on Twitter. These accounts formed the core of the pro-Trump and pro-Clinton Twitter bases: they tweeted at least 15 times with 2 different hashtags of the lists in the week prior to the elections, and the week after.

This key distinction does not come without reason. The filter bubble as we know it is often represented as one big group of like-minded supporters who share the same media. But why not consider the possibility of more deviation within the bubble? Perhaps there’s no such thing as the pro-Trump or pro-Clinton bubble, but are the conventional and fringe groups of supporters really just bubbles in their own right. This, then, is exactly what we researched next.

The results were surprising.

What we found

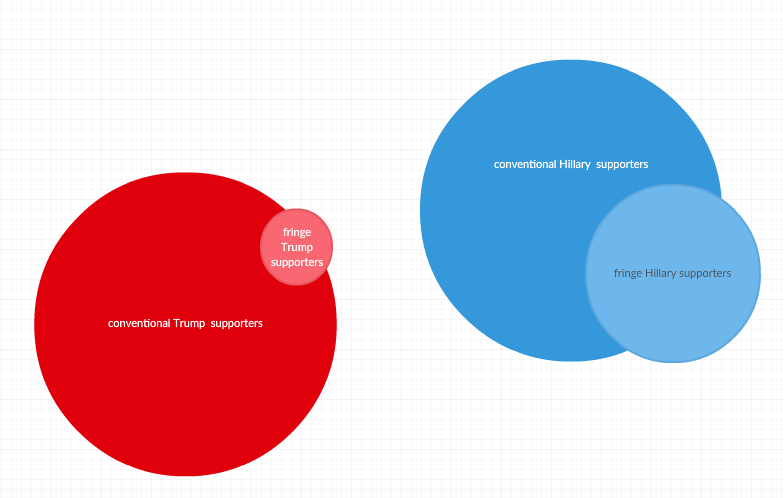

Our first major finding is that, within the group of Trump supporters on Twitter, there’s no such thing as a fringe – or conventional – bubble. The nuance that we were interested in finding, simply doesn’t exist. Despite using different hashtags, either more radical or more conventional, both groups of tweeters constantly share the same media. It was illustrative for our findings that Mike Cernovich, an alt-right leader, did not tweet a single conventional pro-Trump hashtag, but referred to the same media as those in the group of conventional Trump supporters.

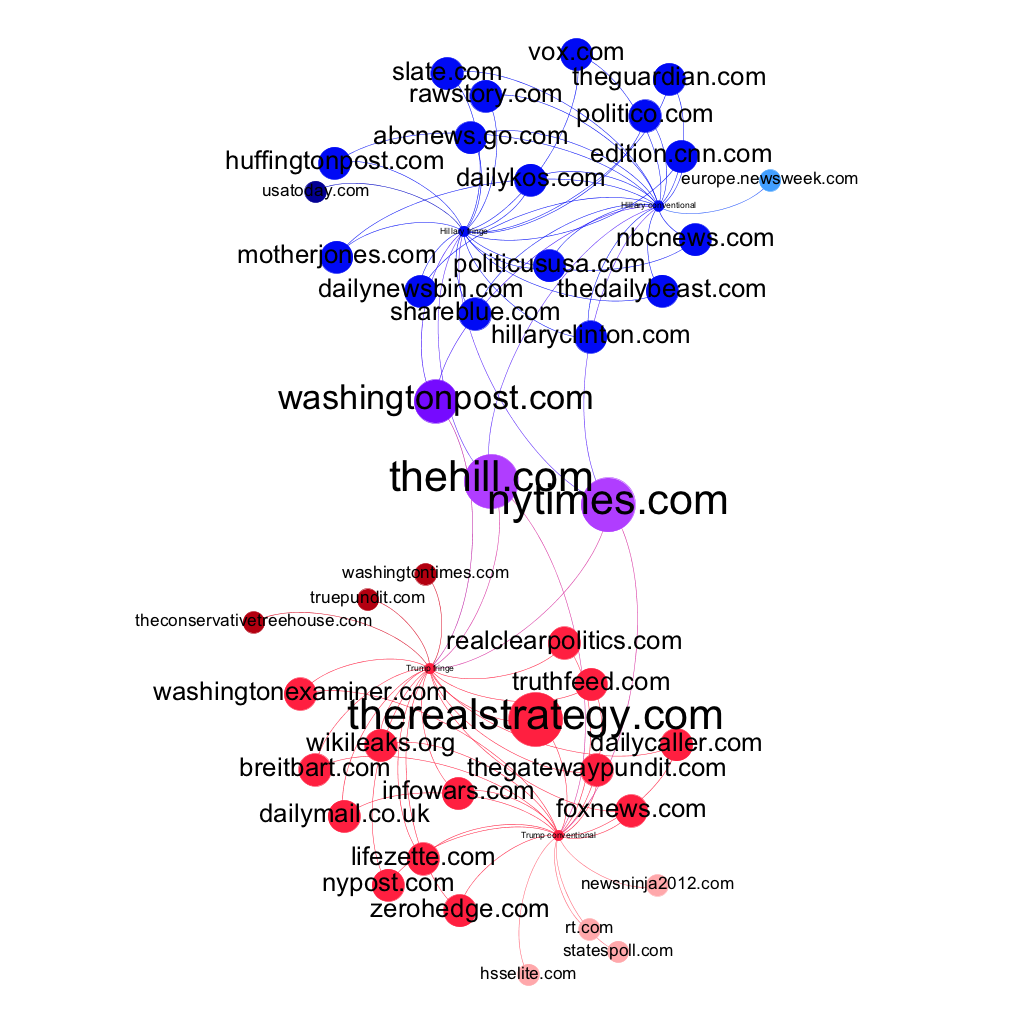

Even more remarkable were the kind of media the Trump supporters kept referring to. Mainstream media were negligible in the pro-Trump bubble. Breitbart and The Real Strategy, a website still writing stories about ‘Pizzagate’, were referred to the most by both conventional and fringe tweeters. Other websites in the top 10 media referred to by both groups separately are The Daily Caller, TruthFeed, The Gateway Pundit, Wikileaks, Fox News, Infowars and the British Daily Mail. To actually find which news media were referred to the most, we decided not to include social media links to, for instance, Facebook in our analysis, as we considered them not representative for our research purposes.

The Trump bubble exists and it is strong. It was remarkable to find that it simply did not matter how radical or conventional a user was in hashtag usage for his reference to media. Moreover, the media that were dominant in the pro-Trump bubble surprised us: not just the mere absence of mainstream media, but the domination of alternative, right-wing websites.

Although the group of pro-Clinton tweeters we researched was significantly smaller than the number of self-identifying Trump supporters, we can pull the same conclusion for the Clinton bubble. We found only 8428 Twitter users with “#imwithher” in their Twitter bio who actively used pro-Clinton hashtags, either conventional or fringe. It seems that people were less willing to self-identify as pro-Clinton, which was also indicated by the number of certain hashtags that were used: the fringe (or anti-Trump) hashtags were used much more than the conventional, pro-Clinton ones.

Even more relevantly, the pro-Clinton bubble appeared much less isolated compared to the overall population of tweeters within our dataset, than the pro-Trump one. Despite having a much smaller core of supporters, the Clinton bubble had a larger overlap in media that were referred to by the non-partisan-identified Twitter users – however not in absolute numbers, as the pro-Trump bubble simply consisted of much more users and tweets. Media such as the Washington Post, The New York Times, The Guardian, and CNN were referred to a lot by both Clinton-supporters and the overall population.

Just three websites were shared by both bubbles: The Hill, and those of the Washington Post and The New York Times.

Yet, as said before, these media were largely absent in the pro-Trump bubble. Established media, such as the New York Times and Washington Post, weren’t regularly mentioned by anyone. It is telling that Breitbart was referred more than ten times as much as to the Washington Post. The total absence of CNN in the Trump bubble is even more remarkable, especially because an analysis of all U.S. election tweets between November 1st and November 15th showed that the CNN website was the most referred to medium on Twitter. The absence of CNN in the Trump bubble is illustrative for its isolation from mainstream, established media.

Yet there was one exception. One story made its way through all sides of the pro-Trump bubble, conventional and fringe, official and alt-right. The story that The New York Times broke about an FBI investigation, which stated that there was no link between Russia and Trump, roamed through the pro-Trump bubble. During the two weeks we have analysed, New York Times story that was shared in the Trump bubble. Something similar can be said for the Washington Post. A story uncovering 1.100 foreign donors to the Clinton campaign was widely shared within the pro-Trump bubble. This was not the only time the Washington Post was referred to, but it moreover accounted for a majority of references.

What does this mean?

We dare say this could expose a seismic shift in how people consume media.

While in non-digital times media influenced opinions, beliefs, and attitudes of citizens through their coverage, our findings might indicate a reverse process. Rather than allowing media to form their opinions, people look within media for confirmation of pre-existing beliefs. People within the Trump bubble were willing to read and share articles from media such as the New York Times or the BBC, as long as they confirmed the beliefs they already had. Trump supporters were more than willing to share the Times article on the FBI investigation, because it confirmed their belief that Trump is not a puppet of Putin. And they were happy to share an article by the BBC, because it confirmed their belief that Clinton should – and will – be “locked up”. People seem to look for messages that confirm what they believe to be true, rather than to look for the actual truth.

The 2016 U.S. presidential elections were a tale of two Twitters. While a large part of Twitter users was in neither of the two bubbles, our results show that bubbles did exist on both sides of the political spectrum. On the one side, a small pro-Clinton bubble, somewhat polarized yet largely in line with the general population on Twitter. On the other side, a massive pro-Trump bubble, characterized by media that are basically never referred to by the general population.

One nation, divided under Twitter.

Research by: Joep Bouma, Jos de Groot, Mathijs de Groot, Mark Lievisse Adriaanse, Sara Polak, Silvana Zorz